Shem Hotep ("I go in peace").

My Son Najee Ishmael Akeem on prom.

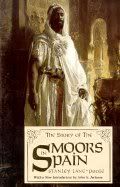

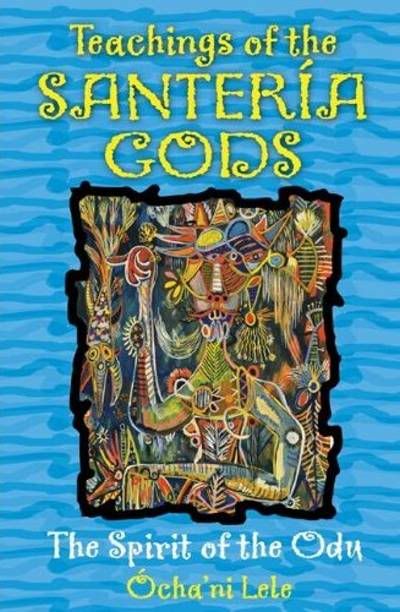

Read the book above.

Read the book above.

Read the book above.

Black Catholics?

Black Catholics? Sounds like an oxymoron, doesn’t it? But it shouldn't. Of the one billion Roman Catholics in the world today, at least 20% (200 million) are Black. Africa alone has 130 million Black Catholics. In fact, the largest Catholic Church building in the world is found in Africa, the cathedral in Yamassoukra, the capital city of the West African country known as Cote d’Ivoire.

During the selection of the last pope, many scoffed at the idea that one of the 12 Black cardinals would be picked. However, it would not have been a first. There have been three African popes: Victor (183-203 A.D.), Gelasius (492-496 A.D.), and Mechiades or Militiades (311-314 A.D.). All of them have been declared saints, that is, the Catholic Church feels certain that all three went to heaven.

The individual most credited with establishing the intellectual and ideological basis of the Roman Catholic Church was an African, St. Augustine who lived around 400 AD. Also, the patron saint of much of Germany, Switzerland and France is St. Maurice. In 287 AD this African general, and his 4,000 African soldiers in service to Rome, refused to attack Christian converts in northern France. For this act of defiance they lost their lives, but their memory is honored even up until today.

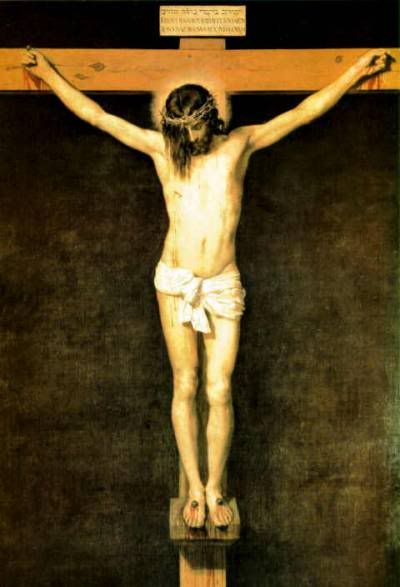

It’s interesting to note there are hundreds of revered icons, that is statues, of Christ and his mother throughout Europe which picture them as Black figures. They are far older than the white depictions of Michelangelo and other Renaissance artists. The last pope, John Paul II, had a Black icon in his personal chapel that he prayed before every day.

Today in America’s inner cities where the public school systems are failing miserably, many Black youngsters are going to private schools to secure an education. Most of these schools are run by the Catholic Church. Also note that there has always been a strong Black Catholic presence in Louisiana. New Orleans’ Xavier University is a prominent, traditionally Black college.

Finally, when the sex scandals hit the Catholic Church full force a few years ago, it was Black Archbishop Wilton Gregory that the Catholic Church in America turned to to handle the controversy. So we see Blacks have been in the Roman Catholic Church from the very beginning. In fact, the Ethiopian Orthodox Christian Church, which is still in existence, predates the establishment of the Roman Catholic Church by more than a 100 years...

African Popes

There were three African Popes who came from the region of North Africa. Although there are no authentic portraits of these popes, there are drawings and references in the Catholic Encyclopedia as to their being of African background. The names of the Three African Popes are: Victor (183-203 A.D.), Gelasius (492-496 A.D.), and Mechiades or Militiades (311-314 A.D.). All are saints.

Pope Saint Victor 1

Saint Victor was born in Africa and bore a Latin name as most African did at that time. Saint Victor was the fifteenth pope and a native of black Africa. He served from 186 A.D. until 197 A.D. He served during the reign of Emperor Septimus Severus, also African, who had led Roman legions in Britain. Some of the known contributions of Victor were his reaffirming the holy feast of Easter to be held on Sunday as Pius has done. As a matter of fact, he called Theophilous, Bishop of Alexandria, on the carpet for not doing this. He also condemned and excommunicated Theodore of Byzantium because of the denial of the divinity of Jesus Christ. He added acolytes to the attendance of the clergy. He was crowned with martyrdom. He was pope for ten years, two months and ten days. He was buried near the body of the apostle Peter, the first pope in Vatican. Some reports relate that St. Victor died in 198 A.D. of natural causes. Other accounts stated he suffered martyrdom under Servus. He is buried in St. Peter's Basilica in Vatican City near the "Convessio."

Pope Saint Victor 1 feast day is July 28th.

Pope Saint Gelasius 1

Saint Gelasius was born in Rome of African parents and was a member of the Roman clergy from youth. Of the three African popes, Gelasius seems to have been the busiest. He occupied the holy papacy four years, eight months and eighteen days from 492 A.D. until 496 A.D. Gelasius followed up Militades' work with the Manicheans. He exiled them from Rome and burned their books before the doors of the basilica of the holy Mary. He delivered the city of Rome from the peril of famine. He was a writer of strong letters to people of all rank and classes. He denounced Lupercailia, a fertility rite celebration. He asked them sternly why the gods they worshipped had not provided calm seas so the grain ships could have reached Rome in time for the winter. He wrote to Femina, a wealthy woman of rank, and asked her to have the lands of St. Peter, taken by the barbarians and the Romans, be returned to the church. The lands were needed for the poor who were flocking to Rome. His theory on the relations between the Church and the state are explained in the Gelasian Letter to the Byzantine Emperor Anastasius. He was known for his austerity of life and liberality to the poor.

There is today in the library of the church at Rome a 28 chapter document on church administration and discipline. Pope Saint Gelasius 1 feast day is November 21st.

Pope Saint Miliades 1

Saint Miltiades was one of the Church's Black Popes. Militades occupied the papacy from 311 to 314 A.D. serving four years, seven months and eight days. Militiades decreed that none of the faithful should fast on Sunday or on the fifth day of the week ...because this was the custom of the pagans. He also found residing in Rome a Persian based religion call Manichaenism. He furthered decreed that consecrated offerings should be sent throughout the churches from the pope's consecration. This was call leaven. It was Militiades who led the church to final victory over the Roman Empire. Militiades was buried on the famous Appain Way.

Pope Saint Militiades feast day is December 10th.

African Saints

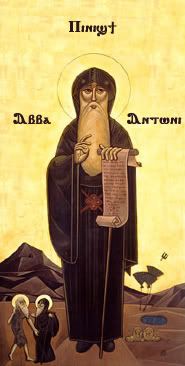

Saint Anthony the Great of Thebes

St. Anthony is called the Patriarch of Monks. He was born at Aama, village south of Memphis, near Thebes. His parents were rich Christians. Shortly after inheriting his parents' fortune, he sold all his vast fortune and gave the proceeds to the poor, sent his sister to a nunnery and retired to an old ruin of a tomb. He ate only every three or four days and spent his time at manual labor and prayer.

Saint Antonio Vieira

Antonio Vieria was an African born in Portugal. When he was fifteen years old, he became a Jesuit novice and later a professor of rhetoric and dogmatic theology. He went to Brazil where he worked to abolish discrimination against Jewish merchants, to abolish slavery, and to alleviate conditions among the poor. On the 200th anniversary of his death in 1897, he was canonized.

Saint Augustine

Historians tell us that there is more intimate knowledge available about St. Augustine than of any other individual in the whole world of antiquity. Augustine the sinner is all too well known. There is knowledge of him as a convert and author of Confessions, but little is known of his as Father of the Church and as a saint.

Augustine was born in the little town of Tegaste, Africa, on November 13, 354. He claimed that he learned the love of God from his mother Monica's breast, and that her early Christian training influenced his entire life. He was highly educated, having studied at Madura, Africa, the University of Carthage, and Rome. He was brilliant - actually a genius, and he used his great abilities to lead men to love God.

His thousands of letters, sermons and tracts, combined with 232 books, instructed the Early Church and have relevance for the Church today. It is said that Christian scholars through the ages owe much to St. Augustine and that the full impact of his psychology and his embryonic theology will be felt in years to come. Augustine was truly a saint. He live an austere life, performing great acts of mortification and penance. He wrote, "I pray to God, weeping almost daily." Two of his most famous books are "Confessions" which is an autobiography and "City of God".

St. Augustine's feast day is August 28th

St. Bessarian

St. Bessarian was born in Egypt. He went to the desert to become a hermit. He is credited for many miracles. Once he made salt water fresh. He brought rain during a drought and once walked on the Nile.

Saint Benedict the Moor

St. Benedict the Moor, a lay brother, was born in Sicily in 1526. He was the son of African slave parents, but he was freed at an early age. When about twenty -one he was insulted because of his color, but his patient and dignified bearing caused a group of Franciscan hermits who witnessed the incident to invite him to join their group. He became their leader. In 1564 he joined the Franciscan friary in Palermo and worked in the kitchen until 1578, when he was chosen superior of the group. He carried through the adoption of stricter interpretation of the Franciscan rule. He was known for his power to read people's minds and held the nickname of the "Holy Moor". His life is austerity resembled that of St. Francis of Assisi.

St. Benedict the Moor feast day is April 4th.

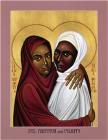

Saints Felicitas and Perpetua

Women persecuted for Christianity at Carthage. Perpetua is recorded for having several visions that depicted her death. At death, she called out to the crowds: "Stand fast in the Faith and love one another. Do not let out suffering be a stumbling block to you…" Felicitas was Perpetua's slave. They died together.

Sts. Felicitas and Perpetua feast day is March 6th.

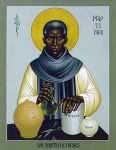

Saint Martin de Porres

On May 16, 1962, Pope John XXIII, in a ceremony at St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, made Martin de Porres the first black American saint. Martin was born on December 9, 1579, in Lima, Peru, the illegitimate son of Don Juan de Porres of Burgos a Spanish nobleman, and Ana Velasquez, a young freed Negro slave girl.

From early childhood Martin showed great piety, a deep love for all God's Creatures and a passionate devotion to Our Lady. At the age of 11 he took a job as a servant in the Dominican priory and performed the work with such devotion that he was called "the saint of the broom". He was promoted to the job of almoner and soon was begging more that $2,000 a week from the rich. All that was begged was given to the poor and sick of Lima in the form of food, clothing and medicine.

Martin was placed in charge of the Dominican's infirmary where he became known for his tender care of the sick and for his spectacular cures. In recognition of his fame and his deep devotion, his superiors dropped the stipulation that "no black person may be received to the holy habit or profession of our order" and Martin was vested in the full habit and took the solemn vows as a Dominican brother.

As a Dominican brother, he became more devout and more desirous to be of service. He established an orphanage and a children's hospital for the poor children of the slums. He set up a shelter for the stray cats and dogs and nursed them back to health.

Martin lived a life of self-imposed austerity. He never ate a meal, he fasted continuously and spent much time in prayer and meditation. He was venerated from the day of his death.

Many miraculous cures, including the raising of the dead, were attributed to Brother Martin. Today throughout South America, Central America and the islands of the Caribbean, people tell of the miraculous powers of St. Martin de Porres. St. Martin de Porres's feast day is November 3rd.

Saint Monica

St. Monica, an African laywoman is a saint with whom most black women can readily and easily identify, because Monica epitomized the present-day black women.

St. Monica was born in Tegaste in northern Africa in about 331. She was a devout Christian and an obedient disciple of St. Ambrose. Through her patience, gentleness and prayers, she converted her pagan husband. To her son, St. Augustine of Hippo, whom she loved dearly, she gave thorough religious training during his boyhood, only to know the disappointment of seeing him later scorn all religion and live a life of disrepute. Before her death, Monica had the great joy of knowing that Augustine had returned to God and was using all his energies to build Christ's Church, and that her youngest daughter had become a nun. St. Monica's feast day is August 27th.

Saint Moses, The Black

Saint Moses, the Black, was a desert monk, born around 330. He was an Ethiopian of great physical strength and unruly character. Moses was a big man and his enormous strength was well known. He belonged to a band of professional thieves and robbers in Egypt. Yet he was a slave Moses always in trouble with the law and his master.

Fearing eventual death from his Ethiopian master, or other criminals Moses ran away into the Scete Desert. No regular people were there, only poor hermits with nothing worth stealing. The hermits converted Black Moses to Jesus; yet his former bad ways held on to him. In order to fight harder for Jesus, Moses moved further into the desert. Soon his conversion to Jesus became widely known. The report reached his former band of robbers. Some of them came and tried to turn him back to crime. He converted them.

He was chosen for priesthood, and at his ordination the bishop remarked to him, "Now the black man is made white". Moses replied, "Only outside, for God knows I am all black within." At age 75, was killed during a raid by Mazics on the monastery, which he refused to defend. He left seventy disciples to mourn him. St. Moses, The Black feast day is August 28th.

Saint Valentine and Dubatatius

Were executed for their faith at Carthage. Sts. Valentine and Dubatatius feast day is November 17th.

Saint Victoria

Died for her faith at Abitene in Proconsular, Africa. Having been arrested for assisting at Mass, she confessed her faith before a judge in 304. She was stretched on the rack and later died in prison.